Brahmagupta

De Wikipedia

Brahmagupta (598–668), matemático y astrónomo indú.

Tabla de contenidos |

Vida y obra

Brahmagupta nació en el año 598 en Bhinmal, ciudad en el estado de Rajasthan, al noroeste de la India. Probablemente vivió la mayor parte de su vida en Bhillamala (moderna Bhinmal, en Rajasthan) en el imperio de Harsha, durante el reinado del Rey Vyaghramukha. Como resultado de ello, Brahmagupta es a menudo citado como Bhillamalacarya que quiere decir, el maestro de Bhillamala Bhinmal.

Fue el jefe del observatorio astronómico en Ujjain, y durante su mandato allí escribió cuatro textos sobre las matemáticas y la astronomía: Cadamekela en el 624, Brahmasphutasiddhanta en 628, Khandakhadyaka en 665, y Durkeamynarda en 672. El Brahmasphutasiddhanta (Tratado corregido de Brahma) es posiblemente su obra más famosa. El historiador Al-Biruni (c. 1050) en su libro Tariq al-Hind, afirma que el califa Abbasid al-Ma'mun, que tenía una embajada en la India, llevó de3 allí un libro a Bagdad que fue traducido al árabe como Sindhind. Se presume que Sindhind no es otro que Brahmagupta-Brahmasphuta Siddhanta.

Aunque Brahmagupta estaba familiarizado con las obras de los astrónomos siguiendo la tradición de Aryabhatiya, no se sabe si está familiarizado con la labor de Bhaskara I, un contemporáneo. Brahmagupta tenía una cantidad de críticas dirigidas hacia la labor de los astrónomos rivales, y en su Brahmasphutasiddhanta se encuentra uno de los primeros cismas de fe entre matemáticos indios. La división fue principalmente sobre la aplicación de las matemáticas al mundo físico, más que sobre las matemáticas en si mismas. En el caso de Brahmagupta, los desacuerdos se debieron en gran parte de la elección de las teorías y parámetros astronómicos. A lo largo de los primeros diez capítulos astronómicos aparecen críticas a las teorías rivales, y el undécimo capítulo está completamente dedicado a la crítica de estas teorías, aunque las críticas no aparecen en el duodécimo y décimo octavo capítulos.

Mathematics

Brahmagupta's most famous work is his Brahmasphutasiddhanta. It is composed in elliptic verse, as was common practice in Indian mathematics, and consequently has a poetic ring to it. As no proofs are given, it is not known how Brahmagupta's mathematics was derived.<ref>Brahmagupta biography</ref>

Algebra

Brahmagupta gave the solution of the general linear equation in chapter eighteen of Brahmasphutasiddhanta,

18.43 The difference between rupas, when inverted and divided by the difference of the unknowns, is the unknown in the equation. The rupas are [subtracted on the side] below that from which the square and the unknown are to be subtracted.<ref name="Plofker Chapter 18 Brahmasphutasiddhanta"/>

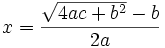

Which is a solution equivalent to No se pudo entender (función desconocida\tfrac): x = \tfrac{e-c}{b-d} , where rupas represents constants. He further gave two equivalent solutions to the general quadratic equation,

18.44. Diminish by the middle [number] the square-root of the rupas multiplied by four times the square and increased by the square of the middle [number]; divide the remainder by twice the square. [The result is] the middle [number].

18.45. Whatever is the square-root of the rupas multiplied by the square [and] increased by the square of half the unknown, diminish that by half the unknown [and] divide [the remainder] by its square. [The result is] the unknown.<ref name="Plofker Chapter 18 Brahmasphutasiddhanta"/>

Which are, respectively, solutions equivalent to,

and

- No se pudo entender (función desconocida\tfrac): x = \frac{\sqrt{ac+\tfrac{b^2}{4}}-\tfrac{b}{2}}{a}

He went on to solve systems of simultaneous indeterminate equations stating that the desired variable must first be isolated, and then the equation must be divided by the desired variable's coefficient. In particular, he recommended using "the pulverizer" to solve equations with multiple unknowns.

18.51. Subtract the colors different from the first color. [The remainder] divided by the first [color's coefficient] is the measure of the first. [Terms] two by two [are] considered [when reduced to] similar divisors, [and so on] repeatedly. If there are many [colors], the pulverizer [is to be used].<ref name="Plofker Chapter 18 Brahmasphutasiddhanta"/>

Like the algebra of Diophantus, the algebra of Brahmagupta was syncopated. Addition was indicated by placing the numbers side by side, subtraction by placing a dot over the subtrahend, and division by placing the divisor below the dividend, similar to our notation but without the bar. Multiplication, evolution, and unknown quantities were represented by abbreviations of appropriate terms.<ref name="Boyer Brahmagupta Indeterminate equations">Plantilla:Harv "he was the first one to give a general solution of the linear Diophantine equation ax + by = c, where a, b, and c are integers. [...] It is greatly to the credit of Brahmagupta that he gave all integral solutions of the linear Diophantine equation, whereas Diophantus himself had been satisfied to give one particular solution of an indeterminate equation. Inasmuch as Brahmagupta used some of the same examples as Diophantus, we see again the likelihood of Greek influence in India - or the possibility that they both made use of a common source, possibly from Babylonia. It is interesting to note also that the algebra of Brahmagupta, like that of Diophantus, was syncopated. Addition was indicated by juxtaposition, subtraction by placing a dot over the subtrahend, and division by placing the divisor below the dividend, as in our fractional notation but without the bar. The operations of multiplication and evolution (the taking of roots), as well as unknown quantities, were represented by abbreviations of appropriate words."</ref> The extent of Greek influence on this syncopation, if any, is not known and it is possible that both Greek and Indian syncopation may be derived from a common Babylonian source.<ref name="Boyer Brahmagupta Indeterminate equations"/>

Arithmetic

In the beginning of chapter twelve of his Brahmasphutasiddhanta, entitled Calculation, Brahmagupta details operations on fractions. The reader is expected to know the basic arithmetic operations as far as taking the square root, although he explains how to find the cube and cube-root of an integer and later gives rules facilitating the computation of squares and square roots. He then gives rules for dealing with five types of combinations of fractions, No se pudo entender (función desconocida\tfrac): \tfrac{a}{c} + \tfrac{b}{c} , No se pudo entender (función desconocida\tfrac): \tfrac{a}{c} \cdot \tfrac{b}{d} , No se pudo entender (función desconocida\tfrac): \tfrac{a}{1} + \tfrac{b}{d} , No se pudo entender (función desconocida\tfrac): \tfrac{a}{c} + \tfrac{b}{d} \cdot \tfrac{a}{c} = \tfrac{a(d+b)}{cd} , and No se pudo entender (función desconocida\tfrac): \tfrac{a}{c} - \tfrac{b}{d} \cdot \tfrac{a}{c} = \tfrac{a(d-b)}{cd} .<ref>Plantilla:Cite book</ref>

Series

Brahmagupta then goes on to give the sum of the squares and cubes of the first n integers.

12.20. The sum of the squares is that [sum] multiplied by twice the [number of] step[s] increased by one [and] divided by three. The sum of the cubes is the square of that [sum] Piles of these with identical balls [can also be computed].<ref name="Plofker Brahmagupta quote Chapter 12">Plantilla:Cite book</ref>

It is important to note here Brahmagupta found the result in terms of the sum of the first n integers, rather than in terms of n as is the modern practice.<ref name="Plofker 423">Plantilla:Cite book</ref>

He gives the sum of the squares of the first n natural numbers as n(n+1)(2n+1)/6 and the sum of the cubes of the first n natural numbers as (n(n+1)/2)².

Zero

Brahmagupta made use of an important concept in mathematics, the number zero. The Brahmasphutasiddhanta is the earliest known text to treat zero as a number in its own right, rather than as simply a placeholder digit in representing another number as was done by the Babylonians or as a symbol for a lack of quantity as was done by Ptolemy and the Romans. In chapter eighteen of his Brahmasphutasiddhanta, Brahmagupta describes operations on negative numbers. He first describes addition and subtraction,

18.30. [The sum] of two positives is positives, of two negatives negative; of a positive and a negative [the sum] is their difference; if they are equal it is zero. The sum of a negative and zero is negative, [that] of a positive and zero positive, [and that] of two zeros zero.

[...]

18.32. A negative minus zero is negative, a positive [minus zero] positive; zero [minus zero] is zero. When a positive is to be subtracted from a negative or a negative from a positive, then it is to be added.<ref name="Plofker Chapter 18 Brahmasphutasiddhanta">Plantilla:Cite book</ref>

He goes on to describe multiplication,

18.33. The product of a negative and a positive is negative, of two negatives positive, and of positives positive; the product of zero and a negative, of zero and a positive, or of two zeros is zero.<ref name="Plofker Chapter 18 Brahmasphutasiddhanta"/>

But then he spoils the matter some what when he describes division,

18.34. A positive divided by a positive or a negative divided by a negative is positive; a zero divided by a zero is zero; a positive divided by a negative is negative; a negative divided by a positive is [also] negative.

18.35. A negative or a positive divided by zero has that [zero] as its divisor, or zero divided by a negative or a positive [has that negative or positive as its divisor]. The square of a negative or of a positive is positive; [the square] of zero is zero. That of which [the square] is the square is [its] square-root.<ref name="Plofker Chapter 18 Brahmasphutasiddhanta"/>

Here Brahmagupta states that No se pudo entender (función desconocida\tfrac): \tfrac{0}{0} = 0

and as for the question of No se pudo entender (función desconocida\tfrac): \tfrac{a}{0}

where  he did not commit himself.<ref name="Boyer Brahmagupta p220">Plantilla:Cite book</ref> His rules for arithmetic on negative numbers and zero are quite close to the modern understanding, except that in modern mathematics division by zero is left undefined.

he did not commit himself.<ref name="Boyer Brahmagupta p220">Plantilla:Cite book</ref> His rules for arithmetic on negative numbers and zero are quite close to the modern understanding, except that in modern mathematics division by zero is left undefined.

Diophantine analysis

Pythagorean triples

In chapter twelve of his Brahmasphutasiddhanta, Brahmagupta finds Pythagorean triples,

12.39. The height of a mountain multiplied by a given multiplier is the distance to a city; it is not erased. When it is divided by the multiplier increased by two it is the leap of one of the two who make the same journey.<ref name="Plofker Brahmagupta quote Chapter 12"/>

or in other words, for a given length m and an arbitrary multiplier x, let a = mx and b = m + mx/(x + 2). Then m, a, and b form a Pythagorean triple.<ref name="Plofker Brahmagupta quote Chapter 12"/>

Pell's equation

Brahmagupta went on to give a recurrence relation for generating solutions to certain instances of Diophantine equations of the second degree such as Nx2 + 1 = y2 (called Pell's equation) by using the Euclidean algorithm. The Euclidean algorithm was known to him as the "pulverizer" since it breaks numbers down into ever smaller pieces.<ref>Plantilla:Cite book</ref>

The nature of squares:

18.64. [Put down] twice the square-root of a given square by a multiplier and increased or diminished by an arbitrary [number]. The product product of the first [pair], multiplied by the multiplier, with the product of the last [pair], is the last computed.

18.65. The sum of the thunderbolt products is the first. The additive is equal to the product of the additives. The two square-roots, divided by the additive or the subtractive, are the additive rupas.<ref name="Plofker Chapter 18 Brahmasphutasiddhanta"/>

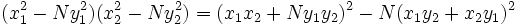

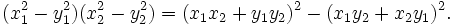

The key to his solution was the identity,<ref name="Stillwell p. 72-74"/>

which is a generalization of an identity that was discovered by Diophantus,

Using his identity and the fact that if (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) are solutions to the equations x2 − Ny2 = k1 and x2 − Ny2 = k2, respectively, then (x1x2 + Ny1y2, x1y2 + x2y1) is a solution to x2 − Ny2 = k1k2, he was able to find integral solutions to the Pell's equation through a series of equations of the form x2 − Ny2 = ki. Unfortunately, Brahmagupta was not able to apply his solution uniformly for all possible values of N, rather he was only able to show that if x2 − Ny2 = k has an integral solution for k =  then x2 − Ny2 = 1 has a solution. The solution of the general Pell's equation would have to wait for Bhaskara II in c. 1150 CE.<ref name="Stillwell p. 72-74">Plantilla:Cite book</ref>

then x2 − Ny2 = 1 has a solution. The solution of the general Pell's equation would have to wait for Bhaskara II in c. 1150 CE.<ref name="Stillwell p. 72-74">Plantilla:Cite book</ref>

Geometry

Brahmagupta's formula

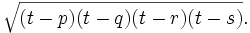

Brahmagupta's most famous result in geometry is his formula for cyclic quadrilaterals. Given the lengths of the sides of any cyclic quadrilateral, Brahmagupta gave an approximate and an exact formula for the figure's area,

12.21. The approximate area is the product of the halves of the sums of the sides and opposite sides of a triangle and a quadrilateral. The accurate [area] is the square root from the product of the halves of the sums of the sides diminished by [each] side of the quadrilateral.<ref name="Plofker Brahmagupta quote Chapter 12"/>

So given the lengths p, q, r and s of a cyclic quadrilateral, the approximate area is No se pudo entender (función desconocida\tfrac): (\tfrac{p + r}{2}) (\tfrac{q + s}{2})

while, letting No se pudo entender (función desconocida\tfrac): t = \tfrac{p + q + r + s}{2}

, the exact area is

Although Brahmagupta does not explicitly state that these quadrilaterals are cyclic, it is apparent from his rules that this is the case.<ref>Plantilla:Cite book</ref> Heron's formula is a special case of this formula and it can be derived by setting one of the sides equal to zero.

Triangles

Brahmagupta dedicated a substantial portion of his work to geometry. One theorem states that the two lengths of a triangle's base when divided by its altitude then follows,

12.22. The base decreased and increased by the difference between the squares of the sides divided by the base; when divided by two they are the true segments. The perpendicular [altitude] is the square-root from the square of a side diminished by the square of its segment.<ref name="Plofker Brahmagupta quote Chapter 12"/>

Thus the lengths of the two segments are  .

.

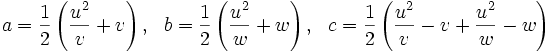

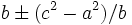

He further gives a theorem on rational triangles. A triangle with rational sides a, b, c and rational area is of the form:

for some rational numbers u, v, and w.<ref>Plantilla:Harv</ref>

Brahmagupta's theorem

Brahmagupta continues,

12.23. The square-root of the sum of the two products of the sides and opposite sides of a non-unequal quadrilateral is the diagonal. The square of the diagonal is diminished by the square of half the sum of the base and the top; the square-root is the perpendicular [altitudes].<ref name="Plofker Brahmagupta quote Chapter 12"/>

So, in a "non-unequal" cyclic quadrilateral (that is, an isosceles trapezoid), the length of each diagonal is  .

.

He continues to give formulas for the lengths and areas of geometric figures, such as the circumradius of an isosceles trapezoid and a scalene quadrilateral, and the lengths of diagonals in a scalene cyclic quadrilateral. This leads up to Brahmagupta's famous theorem,

12.30-31. Imaging two triangles within [a cyclic quadrilateral] with unequal sides, the two diagonals are the two bases. Their two segments are separately the upper and lower segments [formed] at the intersection of the diagonals. The two [lower segments] of the two diagonals are two sides in a triangle; the base [of the quadrilateral is the base of the triangle]. Its perpendicular is the lower portion of the [central] perpendicular; the upper portion of the [central] perpendicular is half of the sum of the [sides] perpendiculars diminished by the lower [portion of the central perpendicular].<ref name="Plofker Brahmagupta quote Chapter 12"/>

Pi

In verse 40, he gives values of π,

12.40. The diameter and the square of the radius [each] multiplied by 3 are [respectively] the practical circumference and the area [of a circle]. The accurate [values] are the square-roots from the squares of those two multiplied by ten.<ref name="Plofker Brahmagupta quote Chapter 12"/>

So Brahmagupta uses 3 as a "practical" value of π, and  as an "accurate" value of π.

as an "accurate" value of π.

Measurements and constructions

In some of the verses before verse 40, Brahmagupta gives constructions of various figures with arbitrary sides. He essentially manipulated right triangles to produce isosceles triangles, scalene triangles, rectangles, isosceles trapezoids, isosceles trapezoids with three equal sides, and a scalene cyclic quadrilateral.

After giving the value of pi, he deals with the geometry of plane figures and solids, such as finding volumes and surface areas (or empty spaces dug out of solids). He finds the volume of rectangular prisms, pyramids, and the frustrum of a square pyramid. He further finds the average depth of a series of pits. For the volume of a frustum of a pyramid, he gives the "pragmatic" value as the depth times the square of the mean of the edges of the top and bottom faces, and he gives the "superficial" volume as the depth times their mean area.<ref>"Plantilla:Cite book</ref>

Trigonometry

Plantilla:Mergefrom In Chapter 2 of his Brahmasphutasiddhanta, entitled Planetary True Longitudes, Brahmagupta presents a sine table:

2.2-5. The sines: The Progenitors, twins; Ursa Major, twins, the Vedas; the gods, fires, six; flavors, dice, the gods; the moon, five, the sky, the moonl the moon, arrows, suns [...]<ref>Plantilla:Cite book</ref>

Here Brahmagupta uses names of objects to represent the digits of place-value numerals, as was common with numerical data in Sanskrit treatises. Progenitors represents the 14 Progenitors ("Manu") in Indian cosmology or 14, "twins" means 2, "Ursa Major" represents the seven stars of Ursa Major or 7, "Vedas" refers to the 4 Vedas or 4, dice represents the number of sides of the tradition die or 6, and so on. This information can be translated into the list of sines, 214, 427, 638, 846, 1051, 1251, 1446, 1635, 1817, 1991, 2156, 2312, 1459, 2594, 2719, 2832, 2933, 3021, 3096, 3159, 3207, 3242, 3263, and 3270, with the radius being 3270.<ref name="Plofker 419–420"/>

In his Paitamahasiddhanta, Brahmagupta uses the initial sine value of 225 with a radius of approximately 3438, although the rest of the sine table is lost. The value of 3438 for the radius is a traditional value that was also used by Aryabhata, although it is not known why Brahmagupta used 3270 instead of the 3438 in his Brahmasphutasiddhanta.<ref name="Plofker 419–420">Plantilla:Cite book</ref>

Astronomy

It was through the Brahmasphutasiddhanta that the Arabs learned of Indian astronomy.<ref>Brahmagupta, and the influence on Arabia. Retrieved 23 December 2007.</ref> The famous Abbasid caliph Al-Mansur (712–775) founded Baghdad, which is situated on the banks of the Tigris, and made it a center of learning. The caliph invited a scholar of Ujjain by the name of Kankah in 770 A.D. Kankah used the Brahmasphutasiddhanta to explain the Hindu system of arithmetic astronomy. Muhammad al-Fazari translated Brahmugupta's work into Arabic upon the request of the caliph.

In chapter seven of his Brahmasphutasiddhanta, entitled Lunar Crescent, Brahmagupta rebuts the idea that the Moon is farther from the Earth than the Sun, an idea which is maintained in scriptures. He does this by explaining the illumination of the Moon by the Sun.<ref name="Plofker 420"/>

7.1. If the moon were above the sun, how would the power of waxing and waning, etc., be produced from calculation of the [longitude of the] moon? the near half [would be] always bright.

7.2. In the same way that the half seen by the sun of a pot standing in sunlight is bright, and the unseen half dark, so is [the illumination] of the moon [if it is] beneath the sun.

7.3. The brightness is increased in the direction of the sun. At the end of a bright [i.e. waxing] half-month, the near half is bright and the far half dark. Hence, the elevation of the horns [of the crescent can be derived] from calculation. [...]<ref>Plantilla:Cite book</ref>

He explains that since the Moon is closer to the Earth than the Sun, the degree of the illuminated part of the Moon depends on the relative positions of the Sun and the Moon, and this can be computed from the size of the angle between the two bodies.<ref name="Plofker 420">Plantilla:Cite book</ref>

Some of the important contributions made by Brahmagupta in astronomy are: methods for calculating the position of heavenly bodies over time (ephemerides), their rising and setting, conjunctions, and the calculation of solar and lunar eclipses.<ref>Dick Teresi, Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science, Simon and Schuster, 2002. p. 135. ISBN 074324379X.</ref> Brahmagupta criticized the Puranic view that the Earth was flat or hollow. Instead, he observed that the Earth and heaven were spherical and that the Earth is moving. In 1030, the Muslim astronomer Abu al-Rayhan al-Biruni, in his Ta'rikh al-Hind, later translated into Latin as Indica, commented on Brahmagupta's work and wrote that critics argued:

According to al-Biruni, Brahmagupta responded to these criticisms with the following argument on gravitation:

About the Earth's gravity he said: "Bodies fall towards the earth as it is in the nature of the earth to attract bodies, just as it is in the nature of water to flow."<ref>Thomas Khoshy, Elementary Number Theory with Applications, Academic Press, 2002, p. 567. ISBN 0124211712.</ref>